When deciding how to organize treatment for “psychosis” we face a crucial question. Should we defer to mainstream views and assume that “psychotic” experiences must be part of an illness? Or should we stay open to the possibility that the confusion and distress we witness may be resulting, not from something wrong with the brain, but from people experimenting with sometimes extreme strategies to cope with difficulties in their lives? And that possibly the confusion and distress we see is created when people experiment with strategies that may backfire in ways they do not understand at the time?

In this post I will be making the case that psychosis is often more of the latter. To illustrate, I will focus specifically on what can happen when people experiment with the competing strategies of skepticism and faith.

Being skeptical, or alternatively having faith, are both examples of strategies people use effectively at different points in daily life. But like a lot of strategies, they can also backfire.

Skepticism involves being able to encounter evidence for something, yet not believe it. So we might read about something in the newspaper, or hear about it from others, or even see something with our own eyes, but yet not believe it is real or at least not be sure it is real.

This is a very helpful strategy when we are exposed to misinformation or partial information, or to sensory illusions or dreams, etc. Of course, it’s not so helpful at many other times, such as when someone is telling us the truth, and we fail to believe them or to act on it in time. Then skepticism backfires.

Faith it seems is an opposite strategy. Faith involves our ability to believe something in the absence of evidence or even when exposed to evidence that the belief is wrong. So we might hold onto a belief that our partner is loyal to us even when confronted by evidence that suggests they are cheating, or hold onto a belief that our business will succeed even when the initial financial reports are dismal.

This is a very helpful strategy say when our partner really is loyal and when it only appeared that they were cheating, or when our business idea is sound but is just slow in becoming profitable. It isn’t so helpful when our partner really is cheating, or when our business idea is hopelessly flawed.

What I’m proposing is that there’s always a tension in our lives between these two strategies, which are designed to meet opposing yet equally valid needs.

One the one hand, we have a need to need to be able to question our beliefs and to be open to disconfirming evidence, so we can avoid continuing to believe what is not true.

On the opposite side, we often have a need to hold on to beliefs in things that are true—even in the face of apparently disconfirming evidence.

But because they are opposites, a dilemma arises. How are we to know when and where to focus on having faith, and when and where to instead practice skepticism? Certainly there are “sources” we might turn to which would tell us, or habits we could follow, but when and where should we have faith in those sources and habits, and when and where should we be skeptical?

One proposed solution to this dilemma might be to define mental health as having just a moderate amount of each: a moderate amount of trust or faith in the media and in other people and in our senses, combined with a moderate amount of skepticism about each of those things.

But I would argue that it’s more complex. Some situations call for more extreme or radical forms of faith, and/or of skepticism. We need to be more extreme to find the truth in some situations that are tricky or where a lot of deceitful evidence may be present. Such situations may exist either for some natural reason, or due to the functioning of a misguided culture or a conspiracy, or all of the above.

For example, imagine the situation of a person who is being told by everyone they know, and by the media, and by mental health professionals, that their depression is due to a lack of serotonin in their brain. To handle that situation well, this person might have to have very strong faith in their intuition that the depression is more a reaction to life events and psychological processes, and to maintain a very firm skepticism about all the social pressure to believe in the chemical story.

One thing I hope you notice in the above example is that there is an interplay between faith and skepticism. To strongly hold faith in some belief, we need to develop strong skepticism about the evidence that contradicts the belief. At the same time, to be strongly skeptical of some evidence, we need strong faith or trust that we can be OK while disregarding the evidence. That gets harder to do when the stakes get higher. An example illustrating such a difficulty was a study where many people would refuse to drink from a beverage labeled cyanide, even after they had been told by the researchers that the label had been applied just to test their reaction to it. It seems they weren’t quite able to doubt or be skeptical about the label when their life was at risk if they were wrong!

As we proceed in life, we are constantly comparing evidence from our own experience with opinions and evidence offered by others in our social world, and then developing ideas about what to believe in and what to be skeptical about. At times, this process can lead us down an unhelpful path, where we get stuck in beliefs in things that aren’t true and being skeptical about things that are true. To get in touch with what is really going on we might need to radically question what we had been believing, and to develop some new belief and then hold onto it even in the face of pressure inside ourselves and from others to revert to a prior point of view. The ability to make such changes in our understanding, or paradigm shifts, could be framed as a kind of superpower. It’s an ability, a feature of our minds, not a defect.

But these same abilities can also lead us into a lot of trouble. They must be used with great discretion to avoid catastrophe. Without that, we might be doubting everything and lost in uncertainty when we might better be following previous ways of thinking, and we might be holding firmly onto radically new conclusions that we would better off questioning.

One curious fact is that psychosis first occurs disproportionately in people who are in their late teens or early adulthood. A possible explanation for this is that this is because the ability to have radical skepticism and radical doubt first develops at this time of life. Just as many types of young mammals go out seeking their own territory at a certain age, humans at a certain developmental stage develop an ability to have an independent point of view, an ability to possibly see things very differently than how everyone else is seeing things.

But a problem can be that these abilities typically emerge when the person does not yet have the judgment to use them wisely. Traditional tales like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice illustrate this kind of situation, where a useful power becomes a big problem when someone does not know how to use it correctly or to stop it.

In thinking about this I’m drawing from my own journey. As a child, I was abused at home and extensively bullied at school, plus I was gay and my community didn’t like that. This led me to have a sense that I was an inferior person, and others around me seemed happy to confirm that.

But there was still part of me that wanted to believe I was OK, or even great! To shift to seeing things that way I had to deeply question a great deal of what I had previously experienced and learned from my interactions with others. So questioning is what I did; but once I started questioning so much of what I had learned and of what my identity had been, it wasn’t obvious to me where I should stop.

We are often told that schizophrenia is an illness where people lose their sense of self, and their sense of a stable world. But I don’t think we talk enough about how such a breakdown can be a strategy like it was for me, an attempt to break free of a sense of self and world that feels or perhaps is inadequate.

One question worth asking is, what happens to our mind when we radically question everything?

It seems we lose our ground, we lose our stability. We can’t trust the media, we can’t trust other people, we can’t trust our memories or our senses. Everything is in doubt.

Where are we then?

A sort of nowhere place, in a great void or question mark or cloud of unknowing. Tumbling in an abyss.

And in a sense, we also seem to be everywhere, because now anything seems possible, anything might be what is “really happening.” Including anything threatening.

Bertrand Russell stated that “Skepticism, while logically impeccable, is psychologically impossible, and there is an element of frivolous insincerity in any philosophy which pretends to accept it.”

Because the loss of a definite world and of an intersubjective sense of reality due to extreme skepticism can be so intolerable or impossible, it’s a common reaction to then go to the opposite extreme, where we grasp at something to believe to give us stability.

But then the danger is that we might grab too firmly, and have faith in the wrong things.

We know that in addition to lacking a sense of self and world, people diagnosed with psychotic disorders often have excessively firm ideas about themselves and the world.

Paul Lysaker once asked someone with a fixed belief why he held onto it so strongly. He answered, “it keeps the vacuum from sucking away my brain.” It seems he was afraid of that emptiness we can encounter when we question everything.

Experimenting with radical forms of skepticism and faith can also lead to inner divisions, conflict, and confusion. People might become skeptical of their own thoughts for example, and start wondering, are those thoughts being put there by someone else? Or skepticism might lead to such a lack of clarity about what to do that when voices emerge that do propose a clear direction, the person might put radical faith in them and act on them without further consideration.

But now let’s consider how the mainstream mental health system typically interacts with people who are struggling with these dynamics.

It essentially tells people to be radically skeptical of their own mind and subjective reality, of their own process of skepticism and faith, and to frame what is unique in their point of view as just “mental illness.” They are pushed to use drugs to reduce the intensity of their independent thinking. And they are asked to radically trust the professionals and others around them to have the correct point of view, even when that strongly contradicts the person’s own perceptions.

This isn’t balanced. It asks people to be mentally passive and to give up on the possibility that their own mental process might be headed toward important truths even when those thoughts and perceptions contradict the viewpoint of others around them. There’s something healthy about resisting the demand for such a surrender of any faith in oneself!

The emerging dialogical approach, fortunately, is quite different. It doesn’t ask people to have extreme skepticism toward their own unique point of view, and such faith in the view of others. Instead it embraces uncertainty and polyphony, which includes the notion that the truth is usually too complex to be held entirely in any one way of viewing it. So there is skepticism about the notion that any person or voice or point of view has a lock on the truth, while also faith that each voice or way of looking at things has some value.

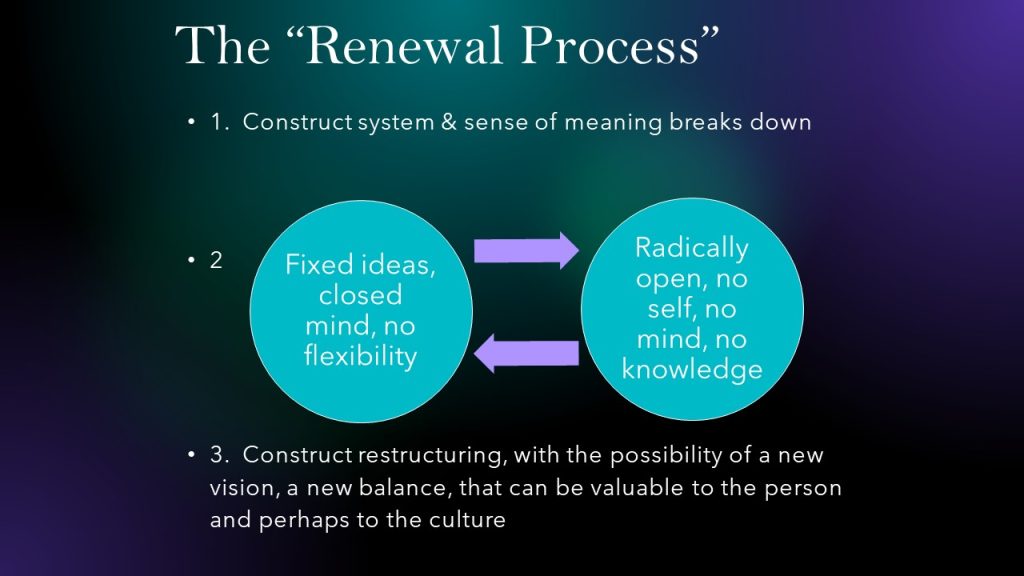

I believe that when mental health professionals take a more balanced or dialogical approach, then people they are attempting to help have a better chance to find a new balance for themselves. With such support, the whole process of going mad has a better chance of becoming something more like a renewal process, or a process of revolution that has a chance of leading to something better, as illustrated below:

We should not be surprised when sometimes young people lose faith in the views of the world they have grown up with and inherited, and with the sense of meaning that they have developed up until that point. There may be something in those views or that sense of meaning that they just can’t stomach anymore, or they may start sensing and believing in the existence of things others don’t acknowledge. They leave a shared intersubjective world, or simply don’t believe in it anymore.

They then enter a middle stage, where they may be exploring extremes and often bouncing between opposite strategies. Radical skepticism may have them in some way lacking a sense of self or a coherent map of the world and, alternatively, radical faith may have them hanging rigidly onto a fixed sense of self and of the world even when that doesn’t work well for them.

At this stage, they may seem lost, and “mentally ill,” and those around them may feel their only hope is to convince the person that they are ill and that they should suppress their own views and surrender to the viewpoint of others. But if this happens, the renewal process is aborted, and the person is left with a sense of having a defective mind.

The saying “when you are going through hell, keep going!” applies here. When we interrupt a person’s radical experimentation and attempt to reimpose an old order, or to have the person frame their own process of breaking away from that order as nothing but illness, people end up in a disabled state. Professionals and family members might hope the person could just go back to being like they were before, but there may be no going back. Instead, the effort to stop the process leaves the person stuck in something like a calm place—in hell.

I suspect one of the reasons why psychosis may then so often “reoccur” is that being stuck in this way eventually becomes intolerable, and the person’s mind again makes a break for freedom—resulting in more chaos.

What is important though is that there is another option. With the right kind of encouragement and support, a person can keep the process of experimentation going, and then often work through their confusion and find a new balance, at a third stage, a stage of return.

In this new balance, they retain their new ability to be radically skeptical of established views and to have radical faith in their own ideas, but they also become able to use some discernment about when and where to invoke these strategies or superpowers. They learn to balance the possible value of breaking away from established views, with the possible value of going along with them and thinking more conventionally. One way of putting this is that they learn to bring their “mad” views into dialogue with more conventional views, a dialogue in which those mad views are still valued, but not overvalued.

This is the return stage of the hero’s journey, where the person comes back to their community typically bearing gifts that resulted from the journey. These gifts can be new understandings and views that may benefit themselves and possibly that can be shared with and revitalize their community.

And our society does very much need to be revitalized! Sadly, what passes for sanity in our society is often not very sane. I’m always reminding people of what my friend David Oaks says, that “normal people are destroying the planet.” And while the process of experimenting with radically different views is dangerous, and often leads to distress and unhelpful views and confusion, it is a critically important process for “questioning normality” that we suppress at our peril.

The better option is to recognize the value of the process, but also find ways to avoid its pitfalls, by keeping the experimentation and the dialogue going till we find something better. One thing that would facilitate this would be creating widespread recognition that it is a process of experimentation, and not an “illness” that needs to be eliminated.

****

Note: This post is based on a talk given at the ISPS International Conference in Perugia earlier this month. ISPS conferences explore new ways of understanding and approaching experiences seen as “psychosis.” The next ISPS-US conference, November 4-6, 2022, will be a hybrid, with options to attend online or in person in Sacramento CA. Discounts for people with lived experience, and some scholarships, are available. Early Bird prices end 10/4/22. For more information or to register, go to this link.

Dear Ron Unger,

My name is Adele Waltari and I am a Master’s degree student, also IFS Level 1 trained. I am currently conducting research about IFS and psychosis for my Master’s thesis. I write to you, because I heard about you from Sascha Altman DuBrul whom which I already collaborated.

So the research is about how IFS therapy can be used in treating psychosis and how we can understand the psychotic experience in IFS concepts.

The study aims to explore IFS practitioners’ understanding and approaches to psychosis. The interview will delve into your experiences, perspectives, and clinical methods in treating psychosis with IFS therapy.

The interview will last approximately 1 hour and will be conducted via video conference.

If you decide to participate in this study, I will provide you with further information about the study and suggest times for the interview.

I look forward to the possibility of collaborating with you.

Thank you for considering this invitation, and I hope to hear from you soon.

Warm regards,

Adele Waltari

Master’s degree student, Psychology department, University of Jyväskylä, Finland

That sounds interesting. I will be emailing you.